NOTE: I wrote this in 1979, one year after my grandfather passed away. I just found this story and decided to share it.

It has been more than a year since Grandpa died. Sometimes I feel as if I have been out of town for a while and when I return home he’ll be there. Painfully I realize Grandpa is gone forever. Immediately the reality of his death becomes a round ball stuck in my throat. Screaming desperately, I call for Grandpa, but the ball is choking me and he can’t hear. “Grandpa, I love you, please don’t go away. Please, Grandpa, try to hold on, fight it, be strong, don’t give in!” Watching his body disintegrate, Grandpa felt he could not win anymore.

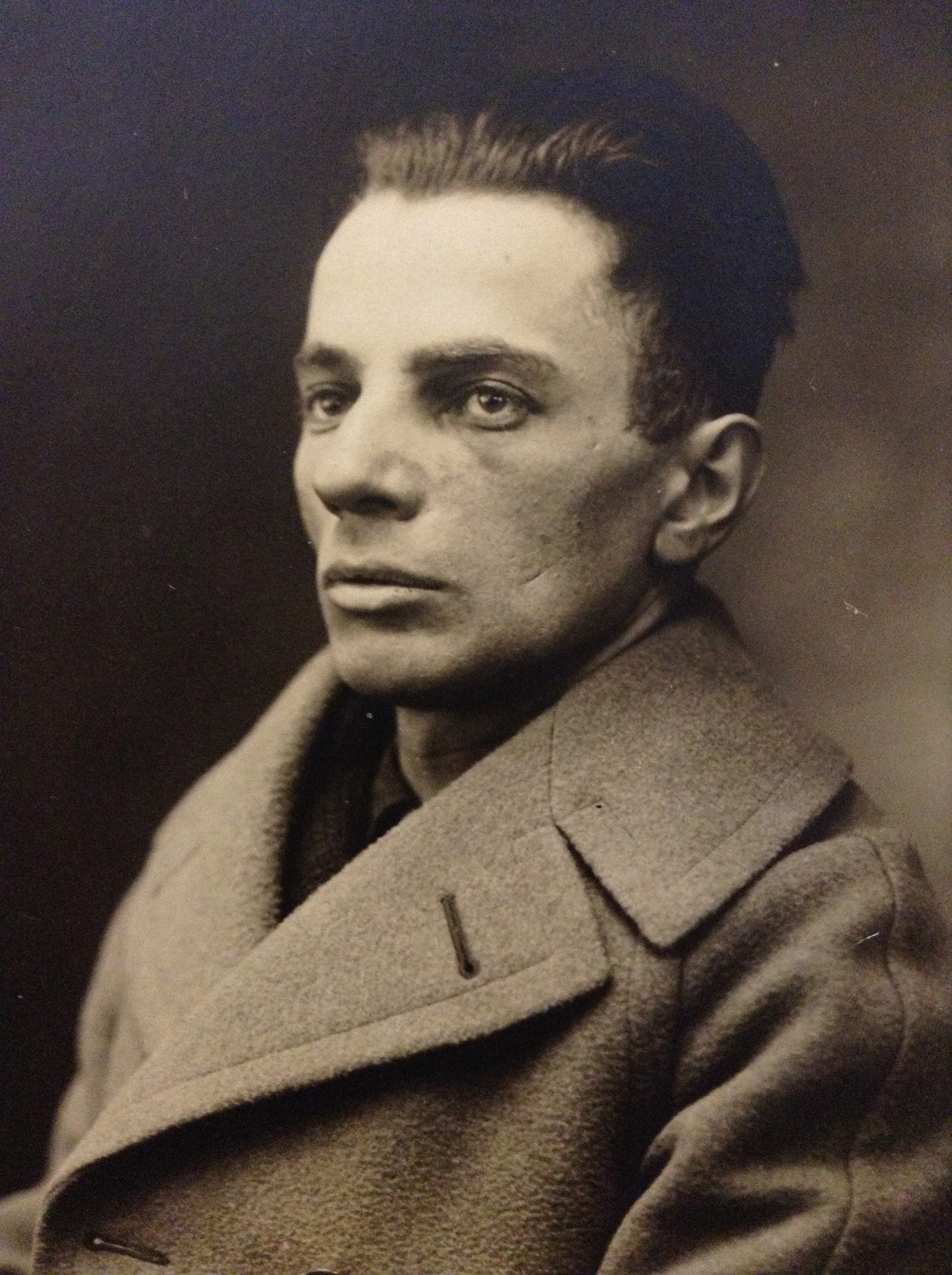

Grandpa was a proud man, never permitting himself to complain. He was that nice old Jewish man who everybody loved. Abey, short for Abraham, was his name.

“Yeah, Abey was an incredible man. He used to come down to the store in the mornings and give us a hand selling the fruit. All the customers loved to buy from him. They’d always walk away smiling.” Pausing for a moment of reflection, the owner of the fruit and vegetable stand continued, “It’s a shame. He was a good man.”

When I was young, we used to go on vacation and take Grandma and Grandpa with us. Grandpa always seemed to be missing. We’d find him standing and chatting with a stranger.

Sitting comfortably on his shoulders was Grandpa's sculptured head. He was equipped with emphatically prominent Russian facial characteristics–high, strong cheekbones and a large, broad forehead with a recessed hairline. Hollowed out below his forehead were sky blue eyes, glowing with tenderness behind, think, dark-framed glasses. Dominating the center of his face protruded a powerfully shaped nose–long, widening at the base with large, carved nostrils. Thin lips sat timidly behind well-kept dentures which filled his mouth. Sparkling teeth gave his appearance a polished look; however, not at all moments. In a fit of speech, Grandpa had difficulty coordinating saliva-swallowing with talking. “Say it, don’t spray it,” I’d yell, wiping the spit off my eyelid. Grandpa’s hair was white, fairly dry, and thick. It was combed by his unique technique–he spat into both hands, rubbed them together, and with alternating hands stroked his hair back and down. Grandpa Abey was always available for demonstrations.

Years ago, Grandma and Grandpa owned a fruit store in Brooklyn. Waking every morning at four o’clock, they’d be standing on their feet working until eight o’clock at night. They were earnestly tenacious, but they barely made a living. Life was a struggle, but Grandpa loved every minute of it. Generous way above his means, Grandpa never could give enough.

How hard it was to watch him die.

Mom and Grandma had it the worst. All the decisions fell on their shoulders.

It began a year after he had surgery to remove the carcinoma found in his stomach. Grandpa’s posture was becoming increasingly bad, bending over further and further.

Grandma would scream, “Abey, Shtay stract!” “Okay,” he’d say, attempting to lift his head up, unsuccessfully. “Oh, c’mon Abey!” she exclaimed.

Poor Grandpa, nobody knew how sick he really was.

We thought perhaps he was bending over because of the stomach surgery. Maybe the scar pulled. We just didn’t know what to think. I used to say, “Grandpa, make believe there is a string attached to the top of your head and someone is pulling it.” Nothing could make him stand straight. Poor Grandpa didn’t know how to describe what he felt.

He began walking more slowly. The energy that had occupied his body was now draining out. Every Saturday morning, he had walked up the hill to schul. That was a holy day, and he would never miss services. However, that walk became more and more difficult, until he just gave up. Grandpa not going to schul on Saturday? We knew that there was something seriously wrong. Snowstorms, pouring rain, heat waves, colds, and fever had never stopped him before.

No matter how many doctors we took him to, nothing showed up. Well, maybe Grandpa was depressed and there wasn’t anything biologically wrong. Poor Grandpa, if only he could have explained.

Abey’s fantastic appetite decreased sinfully. The one-time consumer of three corned beef sandwiches on fresh rye bread covered with mustard, two potato knishes, half a pound of coleslaw, and a bottle of Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray could hardly manage to finish half a sandwich.

When I was a little girl, Grandpa would say to me, “I give ya nickel if ya be a good girl and finish ya essen.” He was referring to the food on my plate. Reminding Grandpa of those times, I’d offer him a quarter to eat up. All the money in the world couldn’t get him to finish. But we didn’t understand why.

I remember sitting on the couch one day with Grandpa when he took my hand and squeezed it. His head lifted to look at me. “I’m sick,” he said softly as his eyes filled with tears. That was the first time I ever saw Grandpa like that. I said, “Grandpa, what is wrong? What hurts you?” He answered hopelessly, “Allas.” “Grandpa, why don’t you eat very much.” I pleaded to understand. “Ich ken nit, I can’t,” he tried to explain; “I’m not hungry.” I felt like my insides were falling out. I wanted to grab him, and hold him in my arms, and make him better. Tears were filling my eyes no matter how hard I tried to fight them. I didn’t want Grandpa to see me crying. I wanted to be strong and helpful, yet I felt so helpless. Grandpa was finally screaming for help and it was me, Grandpa’s little girl, he was directing it to. I cherished him and couldn’t bear to watch him suffer. I didn’t know what to do.

After a short while when my emotions relaxed, I ran into the kitchen to speak with Mom. She told me how many doctors Grandpa had already been to.

“Tomorrow, we have an appointment with another. After they can’t find anything wrong with him, they all ask me how old he is. As soon as I tell them eighty-three, their reaction is, ‘Oh, then it must be old age.’ Gayle, I have even told a doctor he is only sixty-five in hopes of getting an explanation, not an excuse because of his age.”

She was tired and worn out by the situation. The love between Mom and her parents was immeasurable; there was no limit to what she would and could do for them. She had made their lives her complete responsibility.

Mom persuaded Grandma and Grandpa to go down to Florida that winter. Miami Beach had been their retreat for the previous few years and she thought Grandpa would be better off in the warm weather than here in New York during the cold, wet winter. They went.

At first, Grandpa improved. He walked slightly more and gained a pound or two. Then things got worse. At night, he would have difficulty sleeping. Grandma said he would lie on his back staring into space, with his moil off (mouth open), like he’s turt (dead). There were days he never left the room, not even to sit by the pool. He was losing more weight and rarely spoke to anyone.

Mom flew down to Florida. She took Grandpa to see a doctor. Once again, the doctor saw nothing and diagnosed Grandpa’s condition as old age. Mom suggested Grandpa enter the hospital for a few days to undergo a series of tests. No way did Grandpa want to go. He was afraid that he would never come out alive. Maybe Grandpa knew at that time he was dying and wanted his death to come peacefully at home, not in the sterile rooms of a hospital.

Mom decided to fly back to New York and speak to Dad. As soon as she saw Dad at the airport, she ran over to him crying, “Joel, my father is dying and I don’t know what to do.” Mom was under tremendous emotional stress. I had never seen her like that. She was a woman who was always in complete control. Never letting obstacles get in her way, she invariably found solutions to her problems. However, this problem was pulling her apart, ripping her skin off, and leaving her bones naked.

In the middle of the night, Grandpa suffered an attack of acute respiratory arrest. Without much say in the matter, he was rushed by ambulance to the hospital. Spiritually, Grandpa’s life ended then.

Mom and Dad flew down immediately. They found Grandpa lying with a tube down his throat and an intravenous needle in his arm. The respirator was his life support. The tubes, preventing air from passing through his vocal cords, left Grandpa with no means of communication. He couldn’t talk. Not knowing how to read and write, a pen and paper were useless.

A week later, they performed a tracheotomy, inserting a tube through a hole incised at the base of his throat. Supposedly, this system was more efficient, leaving the patient feeling more comfortable and able to speak. Unfortunately, that did not happen. The “trach” still blocked the air passage between the vocal cords and Grandpa’s thoughts were still locked up. It didn’t take words to understand his unhappiness and frustration. He wanted to go home and didn’t care how long he would live without the respirator.

Three weeks later, Grandpa was leaving, but not to go home. He was being transferred back to a hospital in New York. The doctors diagnosed Grandpa’s illness as Lou Gehrig’s disease, an uncommon paralysis of the nervous system that results in death. It was only a matter of time–a week, a month, a year or two. Mom decided it would be less of a hardship for the family if Grandpa was back in New York.

When I heard what the diagnosis was, I rushed to the library to read up on the subject. The medical books described paralysis of the limbs as some of the symptoms. Grandpa didn’t have those signs. Perhaps the doctors had diagnosed his condition incorrectly. I prayed that was so. I just couldn’t believe he was going to die. They made a mistake I kept saying to myself. If only I was a doctor, I thought. As soon as I heard that Grandpa went into the hospital I wanted to fly down and be there, right next to him. But Mom insisted I remain in New York, where she thought I could be more useful. I fought with myself every day until I was resigned to the idea of staying in New York. At night I’d lie in bed meditating about Grandpa, trying to figure out what could be his problem. I didn’t accept amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

All the arrangements were finally made, with great difficulty. They couldn’t fly by an ambulance-equipped Learjet because the compression level was too low for the respirator. The only other alternative was a commercial jet. Eastern Airlines it was. Legal documents were signed both for the nurse and the airline. A portable respirator was rented with two fifty-pound batteries. Grandpa was prepared with a catheter, an intravenous system, and a respirator. A hospital in New York was awaiting his arrival. Grandma, Mom, the nurse, and Grandpa were on their way.

Dad and I met at the airport terminal. There was an ambulance outside, and an attendant with a stretcher stood near us. My stomach had knots in it. I hadn’t seen Grandpa since they had left for Florida. Tears filled my eyes as I imagined his appearance. Poor Grandpa, what have they done to you? All the passengers exited. It was time for us to go aboard. I wiped my tears away, hiding behind my dark glasses. I took a deep breath and proceeded on. Grandma was sitting still strapped into the seat. She had a frightened look on her pale face. It was obvious she had been suffering. Mom and the nurse were running around trying to arrange their departure. Grandpa’s head rested against the back of the seat. His face looked sallow. His cheekbones popped out as the rest sunk in. A tube, similar in style to that of a vacuum cleaner’s except slightly smaller in diameter, was attached to the center, front, and base part of his neck. As soon as he spotted me getting on the plane, a smile reached his lips, an expression he had not worn in a long time. Fighting tears, I approached Grandpa. As I bent over to kiss him he grabbed my hand and pulled me, to kiss my forehead. Looking into his eyes, I saw something special. He had hope. He was going home, or so he thought. Clutching his hand as teardrops fell from my chin, I smiled and said, “Welcome home, Grandpa.”

Grandpa went by ambulance to the hospital with Mom and Dad following by car. I was in charge of taking care of Grandma. She had a great deal of luggage from their five-month winter stay in Florida.

After we arrived at her apartment I undraped the furniture, which had been protected from the dust. Grandma’s nerves looked shot. With a bit of persistence, I convinced her to go to bed and leave the unpacking to me.

As I was sorting the clothing, I came across Grandpa’s little black book. “Birtday, Decembra twenty-eight.” Grandpa would proudly show me how he had my birthday memorized. Then he would ask me to quiz him on the birthdays and anniversaries of family members. He used his little black book as proof. There, he had written down in numbers and simple initials the names and corresponding dates. But Grandpa was always right. He never forgot the date of an important occasion, from any of his children to his great-grandchildren. I didn’t share that attribute with Grandpa.

The following day Grandma and I went to the hospital.

A lump formed in my stomach. This was going to be my first real visit with Grandpa since his illness. Somehow, I felt intimidated and frightened by him. He just wasn’t the Grandpa I knew anymore. What should I say? How should I act? How should I treat him? All my fears made me nervous and anxious.

At the hospital, we met Mom and Dad. Grandpa was in the Intensive Care Unit. Only two visitors were permitted in at a time. Finally, my turn came.

I walked through the first set of swinging doors where there was a woman at a desk. She handed me a visitor’s card. I went through the second pair of swinging doors, bringing me into the IC unit. I looked for Grandpa’s room as I walked, glancing into the rooms I passed. What I saw was no happy sight. A young girl hooked up to machines lay colorless and motionless in bed. She probably was no more than fifteen years old. Her parents sat religiously by her side. The lump in my stomach received little encouragement as I took in those grim scenes.

I spotted Grandpa through the windows of his room. Grandma was sitting at the side of his bed. This was it. There was no turning around now. I had to be brave and grown-up and go to my grandpa.

He was lying in a white hospital gown, falling off one shoulder. A tube was attached to a large machine to the left of his bed, behind his head. That was the respirator. It made a constant thumping sound. How did he feel lying there listening to his life pump up and down? It made me realize that we as humans are machines who sometimes need other machines in order to live. I began to feel grateful for the life I was able to have, independent from mechanical structures. His chest was connected to another machine, which had a heartbeat monitor and also sang its own song. Oh, how could he stand it? How could he just lie there unable to speak, to read, to write, to watch television, which was not permitted in the IC unit? What was he thinking? I had a desperate urge to rip off the invisible tape from his mouth and release his words.

Grandpa’s expression was different from the one he had the night before at the airport. He looked embarrassed and humiliated by his appearance. At the same time, I could see he felt cheated and tricked. This was not his home. Even if closer to home this was just another cold, depressing hospital.

Timidly I walked over to his bed. Careful now to step on the urine bag resting on the floor at the side of the bed and careful not to bump into any of the life support equipment, I leaned over and kissed him. Grandma sat silently. I knew that the talking was now up to me. Awkwardly, I began to speak. “Grandpa, don’t worry. You’ll get better. It only takes time. You’ll be home sooner than you think.” I tried to encourage him, but looking at his skeletal body was enough to make me weep. Grandpa, being a gentleman, tried to smile in response to my words. But it was hard. Nothing seemed to inspire him.

The visits to the hospital became a daily routine. I dashed from work to Penn Station and caught a train out to Long Island, which dropped me off a block from the hospital. There I would meet Mom, Dad, and Grandma. Sometimes other relatives would come. After visiting-hours, we would eat dinner and then I would catch the train back to New York. Grandpa was taken off intravenous feeding. His veins were beginning to collapse. The only nutrition he was able to digest was a high-caloric, sweet drink called Sustacal. The doctors attempted to take him off the respirator too, but that attempt failed. Grandpa’s already skeletal body became worse. The thin layer of skin that covered his body was covered with bruises and sores. Somehow, he managed to sit up in a chair covered with pillows and play rummy with Grandma. Thank God for that. At least there were brief moments he was able to put his mind on something else.

As time went on Grandpa became more and more irritable. He would clap his hands together and put his thumbs down. Grandpa wanted out. Out anyway he could. He just wanted to lie peacefully unattached to any machine or apparatus in the comforts of his home and accept death there. What was the point of living if he had to live like a vegetable? I learned how to deal with Grandpa in his condition. During my visits, I would tend to his hair and cut his fingernails. Sometimes his gown would accidentally separate in the back and fall off. I grew accustomed to seeing his frail, sick anatomy. We would play an occasional game of casino. Grandpa’s mind was extremely alert. He inevitably won the game. The discomfort from the respirator caused him to have choking spells. Very often he sat rocking his head back and forth, probably trying to distribute the pain.

I still found it hard to believe that Grandpa had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. As thin as he was and as sick as he looked, he still maintained a strong grip. His hands were by no means paralyzed, as the medical books described as a symptom.

The nurses who worked in his unit didn’t seem to have any sympathy at all for Grandpa. I remember many times waiting a long time for a nurse to come and adjust his respirator when something went wrong. He was a quiet patient who couldn’t make much fuss even if he wanted to. There seemed to be a common attitude among the nurses and some doctors. Grandpa’s problem didn’t deserve much attention since he was an old man. In fact, for that matter, most people shared that attitude. But he was my grandpa and I didn’t care whether he was one hundred and three or eighty-three years old. I just couldn’t stand to see him die like that. People seemed compassionless. I found it was better not to talk to anybody about him. Otherwise, I would become frustrated.

We gave much consideration to taking him home without the machines. But we decided against it. In the hospital, we thought he’d be safer and closer to any cure if found. It was a difficult decision to make and there were repeated discussions among the doctors and family.

One Saturday I decided I would skip my visit to the hospital and escape to the beach. I had to make one quick stop at my brother’s house to pick up my camera. The phone rang when I was there, and I answered it. The voice on the other end asked me if I was Mrs. Kirschenbaum. I answered that I was Miss Kirschenbaum and asked if I could be of any help. I had a suspicious feeling that this call had to do with Grandpa. With that thought in mind, I started feeling weak. The man on the other end informed me he was the resident doctor at the hospital and that Grandpa had just expired. My first question was, is my grandmother there alone? The answer was yes. My second was, did you tell her he’s dead? He answered yes, again.

After a quick call to Mom, I rushed to the hospital. Mom and Dad had arrived before me. I took Grandma in my arms as she cried. “I was playing cards with him fifteen minutes before.” Grandma had gone down to the cafeteria for lunch when Grandpa died.

There were not many words left to be spoken. I took one last look at Grandpa while they wrapped him in a sheet. Grandpa was a fighter who had gotten tired of fighting. It was hard to believe he was gone forever, but it was a relief to know that he was no longer suffering. Three months had passed for him in that hospital. Three difficult, draining months.

Grandpa was dead. His last wish had finally been answered.

Follow me on Instagram & TikTok @glkirschenbaum. To learn more about my work visit my website.

Thank you for sharing your Grandpa with me ♥ What a great reminder of life being breathtakingly beautiful. Hilda V.

LIKE! Ms Kirschenbaum again has grabbed the reader's attention with heartfelt, dynamic, personal and dramatic story telling! ken c.